Chardham – four questions for the four lanes!

Chardham pilgrimage is an important and integral part of Uttarakhand tourism. An ambitious chardham road renovation project in underway. But at what cost? And for whom? I have four simple questions for which I seek simple answers.

Chardham stands for the four pilgrimage centres – Gangotri, Yamunotri, Badrinath and Kedarnath. Lakhs of national and international pilgrims visit these holy destinations every year. Over the years, not only the numbers but the attitude of the visitors has also changed. Many of the visitors are ‘tourists’ who visit these holy shrines to get respite from the scorching heat of the plains.

The roads leading to these pilgrimage sites are being renovated with an initial budgetary allocation of 12000 crores. The renovation entails making the road 10 metres wide for a stretch of 900 kilometres. The stated objective is to make this ‘strategic road’ an ‘all-weather road’.

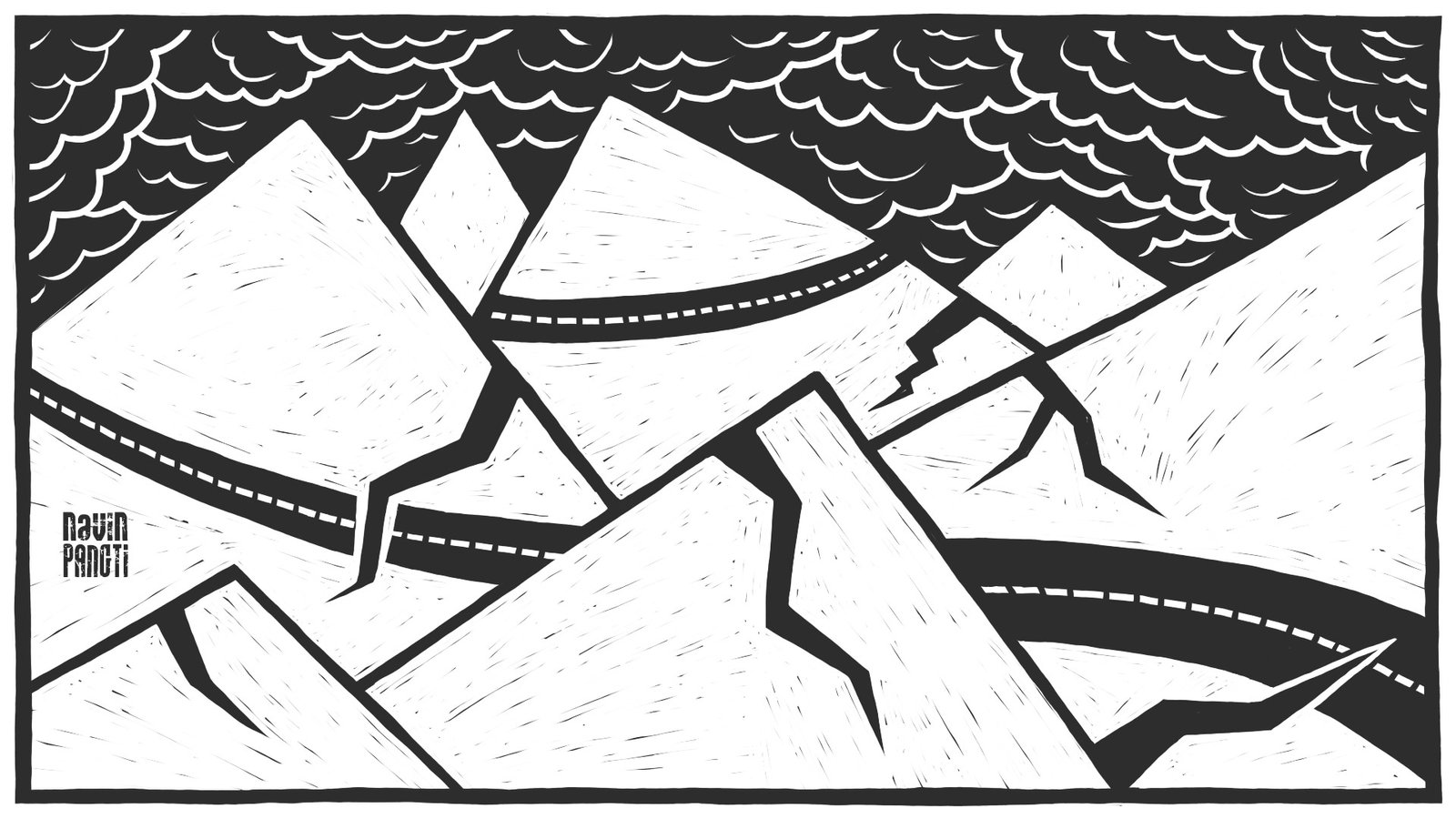

As the roads do not float in the air, mountains and trees are being cut indiscriminately. Hence a writ petition was filed in the Supreme Court to curtail the illegal cutting of trees. The Supreme Court responded by forming a High Powered Committee (HPC). This 26 member committee was to inform the court and the government about environmental viability of the project. As the HPC proceeded with its inquiry, the committee split into two. The chairman of the committee, along with three colleagues, became minority in the committee he was heading. This led to submission of two conflicting reports. Thankfully the Supreme Court validated the chairman’s version of the report.

While the matter was sub judice, the incessant rains lead to landslides and human causalities. While some labelled these casualties as ‘natural disaster’, others termed them as institutional murders in the name of development. What is surprising is that the environmentalists too split into different ‘camps’– some opposing the motion, some supporting and some sitting quietly in their comfortable corners. If one digs deeper into the nuances of these stances, one will realise that the real issue is not about opinions but about the colour of the glasses one is wearing. Some glasses are coloured with ‘academics’ while some have lost focus due to personal or political compulsions.

One of the biggest causes of confusion is the obsessive compulsion of specialists to ‘find’ and ‘analyse’ something ‘special’ as per their ‘specialisation’. Such compulsions also stop them from exploring systems based viewpoints. No wonder each ‘specialist’ is holding a different body part of the elephant in the room and paraphrasing his/her questions based on that. Hence, instead of the core issue, the questions themselves have become a point of discussion, while the elephant stands utterly confused.

Frankly speaking, the chardham road project is not just about trees being cut and mountains being torn apart, illegally. Converting anything ‘illegal’ into ‘legal’ is not a major challenge for any government. If, what we are calling ‘illegal’ today, gets legislated as ‘legal’ tomorrow then which court will we move? What options will we explore to stop the wrong from being done?

Many a times, the ‘expert’ concerns pertaining to the issue themselves come across as questionable. For instance, the HPC is ok with ‘some amount of road widening’, the extent of which it wants the courts to decide. What does one conclude from such a stand?

I feel that many a times our ‘experts’ avoid the core questions, which are usually the simplest and the most logical questions. I am sharing the questions that immensely bother me with regards to the chardham project, and all other similar road projects undertaken across the Himalayan range. I hope that these questions will not only trigger logical debates, but also help us reach viable conclusions.

Question 1

Is the road being built for ‘strategic’ reasons?

The issue of ‘strategic importance’ of the roads is raised pretty often. If the road is indeed of strategic importance then it should be built. But what is the strategic importance that we are talking about? Is it the China threat?

The same logic is used to justify a road to my far-flung native village Milam. I am yet to understand this line of thinking. I often wonder whether we are living in ancient or medieval times that the Chinese army will invade India through the treacherous passes of the borderland and capture the bordering villages. Will they be foolish enough to waste their energy into capturing villages whose governance from across the border is literally impossible? If this was even a distinct reality then there would have been at least one instance in history when these bordering villages were under direct Tibetan rule.

In an eventuality of an indo-chinese war, one can rest assure that the war is not going to happen on these high Himalayan passes. We also need to remember that the roads that lead us to the border also grant easy access to the invaders. Another important point of ponder is – If there is indeed a threat then how come these borders are not guarded with same zeal as some other borders of the country. Why do we not have a significant army presence to ensure quick response along these borders?

I think it is important that we discuss and analyse this ‘strategic need’. If there is no real strategic need then the first argument favouring the widening of these roads stands annulled.

Question 2

Is it road being built to enhance tourism?

In the year 2019, approximately 12 lakh pilgrims visited Badrinath and Kedarnath hosted about 10 lakh pilgrims. This pilgrim influx is not evenly spread. While the influx during some months, especially summers, is overwhelming, there are many months that hardly witness any footfall.

To analyse the visitor load, let us assume that pilgrim influx is evenly spread which means that approximately 1 lakh pilgrims visit Badrinath every month, an average of 3500 visitors per day. Data shows that the number of pilgrims increases by 1.5 to 2 lakh visitors per year, a trend for the last 5-6 years. This means that there is a yearly increment of 500 in the average daily figures.

Looking at these numbers, it is easy to conclude that beyond the issue of cutting trees and pulling down the mountains, there exists a more fundamental question – are these pilgrimage sites and their neighbouring villages capable of bearing the load they are being subjected to? Has anyone analysed this load and its impact? Is there any plan to mitigate the risks and overcome the ill-effects of such overwhelming visitor load?

The envisioned four lane road is designed to get more people to the holy sites at a faster pace and with much ease. Imagine 3500 people visiting the holy sites every day. Even if each one of them drinks 2 litres of water per day and goes to the toilet twice a day, there is a per day requirement of 7000 litres of potable water and 50,000 litres of water for the toilets. Toilet waste of at least 5000 Kgs will also be generated every day, which will have to be safely disposed. And we are yet to talk other wastes, pollution, etc.

What is our collective view of this rather optimistic data? Any discourse on the environmental impact of these visitor movements?

On one hand we are unable to efficiently deal with the current visitor load, on the other hand we are trying to find ways to maximise the influx. It is hard to imagine what are we gunning for? What do we want? Have we forgotten unbearable Kedarnath tragedy? Why are we trying to accelerate at a time when the real need is to restrain or deaccelerate?

If the time is indeed ripe for bringing in control mechanisms then the second argument in favour of widening these roads stands annulled.

Question 3

Are we building an all-weather road?

One of the aspects of the road widening project is to construct ‘all-weather’ roads. Going by this logic, a wide road is perennially accessible. What this in turn means is that a wide road is not affected by landslides or does not invite landslides, even when thousands of trees are being chopped and a god-knows-how-much metric tonne of mountains are being dislodged to widen these roads. How can one be so illogical? When the experts shift the road discourse to carbon release, it is tough to figure out where the catch is? Why can’t our experts simply, clearly and definitively talk about the real issues at hand instead of wandering all over the place?

Ask anyone who dwells in the mountains. She will tell you that the all-weather road is the one which is free of landslides. And those areas are free of landslides where trees have not been chopped and mountains have not been excavated. Why will landslides not happen if the mountain rocks are dislodged through senseless use of heavy earth movers, especially when it is yet not possible to alter the rule of gravitation through a government order?

And then we have this childish insistence to make ‘straight’ roads near the river beds in spite of several instances where the riverbed got raised due to the construction rubble, aiding the monsoon deluge in washing down of the same road which created the rubble.

To be honest, our public works departments have not even understood the role of water channels along our roads. Even mild showers lead to formation on moon craters on our city roads and highways. In such a scenario, it is impossible to guess the philosophical and scientific assumptions behind an ‘all weather’ road.

If this widening of the roads is nothing but a political, bureaucratic or commercial persistence then the fourth argument favouring the widening of these roads stands annulled.

Question 4

Who road is it anyways?

Let us now deal with an even more basic question – Whose road is this? For whom is any road built or widened? Who gets displaced to make way for these constructions? Whose house falls apart? Who is losing their loved ones due to such ‘developmental’ activities? Do these roads belong to these sufferers as well? What is the opinion of a common citizen of Uttarakhand which regards to these roads and their ownership?

The truth is that people have always been told that roads usher development. This has been told so many times that people too seem to have started believing in this gospel truth. The term road has almost become synonymous to development.

Many environmentalists have perhaps chosen to stay silent due to such perceptions of the common man. They do not want to disturb their delicate relationship with the people. They also fear that if they speak out, they will be subjected to political mudslinging – which they are either scared of or simply want to avoid. Their decision maybe logical but it does not stand the test of professional morality. When information and logic start fearing the ‘majority’, environmental degradation is unavoidable.

Similar to the ‘Whose road is this?’ question is another important question ‘Who is Uttarakhand?’ or ‘To whom does Uttarakhand belong?’ If only the majoritarian power of the plains or commercial interests of greedy contractors and businessmen going to define and shape the future of Uttarakhand then there is no space left to raise valid environmental arguments?

Hence it is necessary that the inhabitants of Uttarakhand raise these questions. Because they are the people for whom the road is apparently being built. As all the resources are being allotted in their name hence they have every right to ask questions. But if the mountain residents are going to singularly lean on the shoulders of environmentalists and civil society for raising these important questions on their behalf then the question of environment is bound to be sacrificed on the altar of majority opinion and economic greed.

But if the residents of the Uttarakhand are willing to ‘own’ the road, and through the power that vests on them due to this ownership, disown the widening of the road then the fourth, and on the most important, argument in favour of widening of these road stands annulled.

Brilliant Hem! It is comprehensive and has a lot of seriousness. Another question could be, where was the demand.

I will write more about it later on.

Very insightful raising serious concerns. Besides, the last question is making me wonder how public interests can be realised by the masses themselves in a time when humans are encircled with needless (many a times manufactured) content and information from social media to television. This web of misleading content and information by different sources seeking their self-interests is surely another worrisome issue to come to grips with in order to awake the commons.

Very Nicely Put !

If only this could be poured into some worthy ears 🙂